The American Leftists and Solidarity with Ukraine

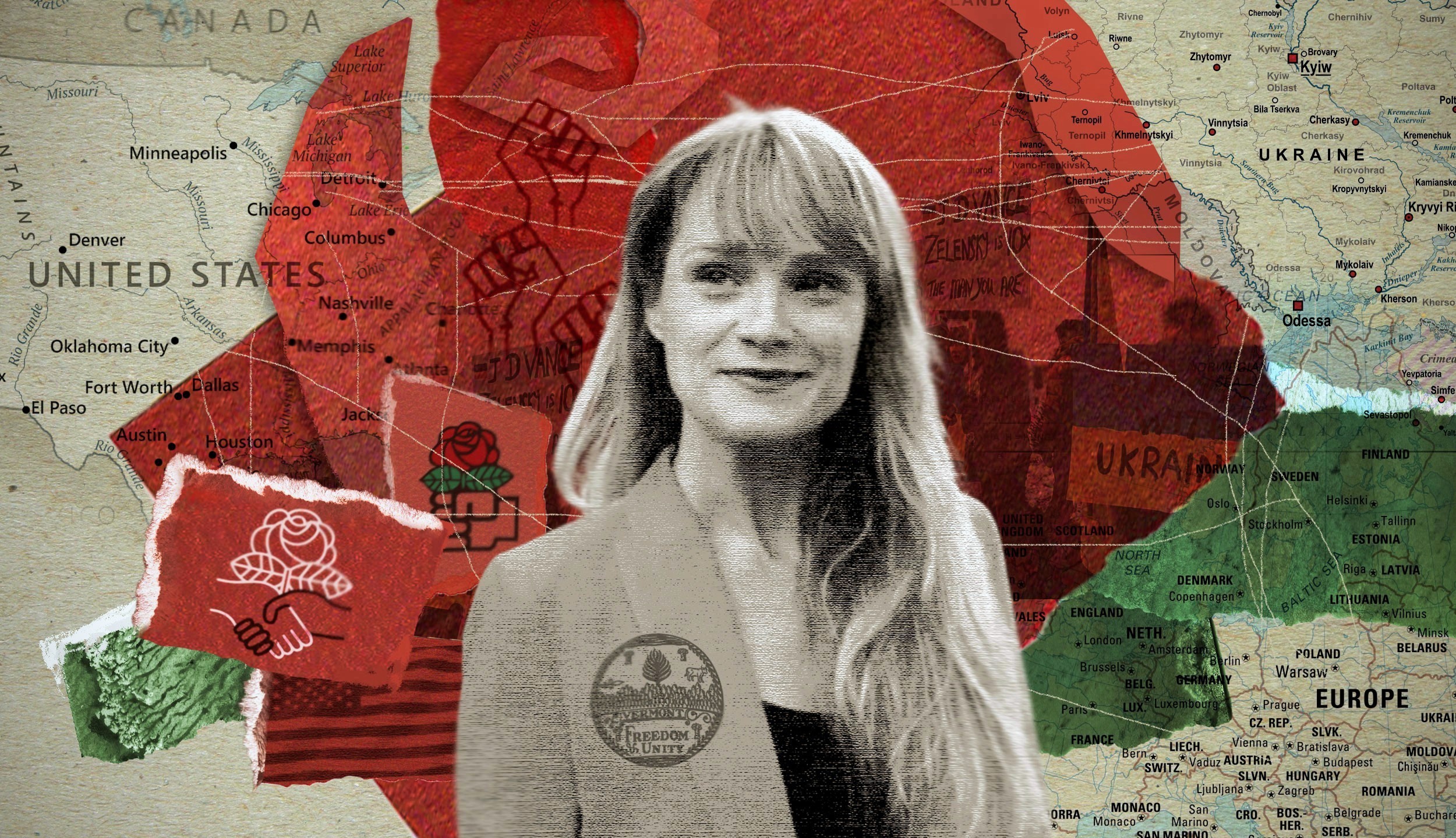

How does American exceptionalism play against solidarity with Ukraine among the American left? Is it possible to combine an anti-militarist position with support for Ukraine? Ilya Budraitskis discussed these issues with Tanya Vyhovsky, a Vermont state senator and Democratic Socialists of America

— You are probably the only American politician of Ukrainian descent with progressive views, and this combination seems rather unusual in the American context. Tell us a little about your background, your path to activism, and work in the Vermont State Senate.

— Yes, absolutely. It has been noted by many that it is a somewhat unusual combination of characteristics. I was born into a working-class family. My dad is Ukrainian — his father was from Ukraine, and his mother was from Hungary. She actually left Hungary when she was 15, during the revolution in 1956. I spent a lot of time with my grandmother while I was growing up, because my parents were very young. So, a lot of the conversations that we had around the dinner table, I think, were profoundly different from the conversations a lot of my American peers were having — particularly in terms of understanding what fascism looks like, and what it is like to live under occupation. Both she and my dad really raised me with a strong set of values that everybody deserves to have their basic needs met. And I think those kinds of leftist values were really instilled in me from an early age. I did not really know what they were, that that is what it actually was. It was just so core to how I grew up — in our conversations, how we discussed and talked about what was happening in the world. I also think one of the unique parts of my upbringing, different from most Americans, was that I traveled a lot. I got to see other places and see that there are other ways of doing things in the world.

When I finished university — this was before the Affordable Care Act — I was deemed uninsurable by my workplace's health insurance because I had preexisting conditions from my childhood. And that is what really pushed me to become a community organizer. I plugged in here in Vermont with the Vermont Workers’ Center and the “Healthcare is a Human Right” campaign. I did a lot of community organizing there, which started to put me in contact with other community organizers and helped me find some real language around what my beliefs and values were. I have also spent my entire professional career in human services and really started to recognize how much our systems were failing people. And I think that eventually led me to run for office, doing it from a community organizer standpoint. I am one of those who look at the government’s structures and frameworks here and really across the globe and want them to work for everyone.

And it is not usually people like me who are elected in office. It is not usually working-class renters,

people who are struggling with the same day-to-day things that the majority of people are struggling with. There is not usually a seat at the table for them. So, there was kind of a wide, winding path that brought me to this point. But I think, again, it comes down to the core values of people who raised me and spent a lot of time with me when I was young, developing my sense of the world and what is important. It has since allowed me to connect more globally with leftists, with Ukrainian leftists, and with people who really share my view that a better world is possible, but only if we stand together and fight for it.

— According to recent polls, more than half of Americans believe that support for Ukraine, including military aid, is necessary. At the same time, the majority thinks that the war should end through negotiations between Russia and Ukraine, with the participation of the US. However, it is clear that attention to the war has declined significantly against the backdrop of the ongoing genocide in Gaza. How would you assess the dynamics of American society's attitude toward Ukraine and its right to resist aggression over the past three years? And what role have Trump's months of unsuccessful attempts to mediate a peace agreement between Ukraine and Russia played in this?

— I think you are right that this kind of attention has declined. One thing I have noticed, with pretty much every issue, is that the American’s attention span is short. I remember — it must have been March of 2022 — organizing with a small network of Ukrainians living here in Vermont, along with our federal delegation, to do a rally and an event at the State House. People were like, “Oh, we should push it out till it is warmer.” And I — very cynically, but unfortunately, correctly — said, “You know, people are not going to be paying attention to this when it is warmer.” Like, right now, all eyes are on this because it just happened, but there will be a next disaster that draws people's attention away. And I think that is exactly what we have seen happen as the focus shifts to the next crisis.

I also think that, yes, we should be talking about the genocide in Gaza. We need to be talking about all of these things. I would argue that, in some ways, there is genocidal behavior happening in Ukraine that we are not talking about. The Russians are kidnapping Ukrainian children and trying to take away their Ukrainian identity. Stories about political prisoners who are beaten for speaking Ukrainian — those are genocidal actions and an attempt to take away culture and identity. And I do not want to get into the sort of Olympics whose suffering is worse. I think we have to be able to talk about all of these things. If we are truly going to stand in global solidarity for a better world, we have to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time.

We have to be able to recognize that there is a genocide in Gaza and that the Ukrainian people deserve to defend their sovereignty. Those things can be true at the same time.

What I think has happened in the months since Trump took over is that a lot of Americans have actually recommitted to their support for Ukraine. They saw that disastrous meeting where Donald Trump attacked President Zelensky. And what it really did was remind people that there is this war going on and this horrific partnership between Putin and Trump, as the world marches toward global fascism and global authoritarianism. So, I actually think that, in some ways, that has brought the issue back to the forefront, back to the surface, more so than it really had been for the past three years. And it is still really complex. I think there has been a large, organized movement to keep the Palestinian struggle at the forefront of people's minds, which has not existed as much and has not been as unified, when it comes to keeping the Ukrainian struggle at the forefront of people's minds.

— From the very beginning of the full-scale war in Ukraine, a significant portion of the American left has effectively repeated Putin's narrative, according to which the Kremlin's aggression is actually a form of self-defense by Russia against the threatening imperialism of the US and NATO, while Ukraine is in fact a Western colony, whose power is, moreover, in the hands of neo-Nazis. This primitive explanatory scheme, based on an extremely superficial understanding of both the Ukrainian and Russian political situations, has proven to be very persistent and is largely unaffected by factual arguments. What do you think these attitudes are related to? And is it possible to change them in any way?

— So, I think there is probably a mix of factors that bring this attitude into leftist spaces. It is incredibly difficult to break through them. What we know from sociological studies is that when people believe something that they have been propagandized to believe, giving them facts actually tends to make them dig in even deeper rather than bring them out of it. What is far more effective is connecting on some personal level or some moral level and then helping connect that to the issue. It is possible, though probably not for everyone. I think there are some individuals who are going to stand on that hill and stay on that hill, but I do not think that everyone who has been propagandized in that way is a lost cause. I think it is about how we connect with people — how we help change that narrative, help them understand the history, and help them understand what is going on by connecting them to real people who are on the ground, who are there, who are experiencing it, who are living it.

The last three and a half years have been an incredibly painful experience as a Ukrainian-American leftist in leftist spaces. Certainly, I think some minds have been changed, and there have been spaces where I — because it is personal to me — have been able to connect with people and help them to see me as fully human, and through that connection, begin to look more deeply into their understanding. There have been other people with whom I have just had to say, “No, I cannot do this.” I do not have the emotional energy or capacity to engage in this. And that varies from day to day, from moment to moment — how much capacity I have.

I think the more we talk, the more we connect, the more open we can be, the more capacity we have to change that.

I also think that some of these beliefs are grounded in American exceptionalism.

But on the other hand, there are people who believe that anything the U.S. does is bad. If the U.S. is supporting this, it must be bad, it must be imperialism. This view is overly simplistic and fails to recognize that what we are actually seeing is Russian imperialism.

While I hold no illusions that the United States was supporting Ukraine for altruistic reasons, I do recognize that what Russia was doing was imperialism and the occupation of a sovereign nation. That is always wrong. So, I think there is a lack of nuance and understanding. And I think that, in some ways, this is intentional. I mean, the United States has for many decades disinvested from civics education and from building the critical thinking skills that help people see that nuance. It is almost a sort of reactionary stance. There is the American exceptionalist view that everything America does is amazing. And then there is this sort of reactionary left-wing view that, no, the absolute opposite must be true. These positions exist without recognizing that, actually, most of human experience exists in the gray area, not at the extremes.

The messaging about neo-Nazis has been particularly troubling. I mean, all of it is troubling, but this is especially concerning — because it is so deeply rooted in a misunderstanding of what these words even mean. Yes, there are Nazis in Ukraine, but there are Nazis in the United States, too. In fact, some are in the White House. When I look at the numbers of how many of those far-right Nazis in Ukraine ran for office and won — it is zero, by the way — versus how many are sitting in office in the United States, I think we, as the left, have to do some reflection. There are Nazis everywhere.

— In fact, there are a lot of American Nazis who support Russia and admire Putin.

— Yes, certainly. And actually, I have been reading through some speeches by Russians who have been arrested and are political prisoners for speaking out against Putin. Many of them name the Nazis in Russia who are in power. So, it is just such a false narrative, grounded in no real understanding of what imperialism is or what fascism is.

Sure, there are some Nazis in Ukraine, but the Ukrainian people do not deserve the occupation and imperialist fascism just because some people identify with far-right views. And to your point, there are far more of those people in positions of power here, in the United States, who actually support Russia. So, the factual basis of these arguments is just frustrating to me sometimes, because of the mental gymnastics you have to go through to make absolutely any logical sense of them.

— One of the most difficult issues related to the war in Ukraine is the problem of military aid. On the one hand, Ukrainian cities are being barbarically bombed every day, and the Russian army continues its offensive regardless of casualties, making further military supplies vital for Ukraine. On the other hand, left-wing and progressive forces have traditionally opposed the U.S. military intervention in other countries and the strengthening of its military-industrial complex. Is it possible to combine an anti-militarist position with support for Ukraine today, especially with demand for the US government to continue this military aid?

— I think this is one of those spaces where people refuse to live in the gray area where reality is. I would consider myself an anti-militarist, an anti-war peace advocate. But I also believe that allowing an imperialist aggressor to take over a country does not lead to peace. In fact, it is going to produce growth of militaristic actions. If imperialist Russia is able to go in and take away Ukraine’s sovereignty, there is no world in which they stop there. We already know this. We know this from 2014, when Crimea was annexed. Then we were like, “Okay, as long as you stop there.” But, of course, they did not, and they will not.

And so, I think this sits in this sort of nuanced space. “No, I don't want war,” versus simply saying, “Sure, you can come in, attack, and take the sovereignty of this nation” does not produce lasting peace. If Russia were to stop fighting in this war, the war would be over. If Ukraine stops, there is no more Ukraine. And those are different spaces that you stand in. And sure, I would love to live in a world where there was no war, but that is not the world that we live in. And asking a sovereign nation to give up its land, to be occupied, to once again live under the oppressive occupying force of another country — that is not peace.

I mean, we see that again, and this is what we have been asking the Palestinians to do for over 70 years: to live under occupation, to be occupied by another military power. It does not produce peace. It has not produced peace in Gaza. It will not produce peace in Ukraine. It will not produce the global peace that we need. And so, when I think about how to advocate for giving Ukraine the support it needs to end this with a Russian military defeat, that, to me, is a better path toward actual global peace. And then, of course, we have to go in and begin doing the relational repair work, doing the solidarity work, and doing the work to ensure that the Russian people can also overthrow their fascist government.

But I do not see allowing Ukraine to fall as a movement toward anti-militarism. I see it as a movement toward anti-democracy.

— We have already discussed this briefly, but Ukraine and Gaza are currently the scenes of two of the bloodiest and most genocidal conflicts of our time, but it is extremely difficult to imagine a single movement of solidarity with the Palestinian and Ukrainian peoples in America today. What parallels do you see between these wars? And how can this be brought to the attention of American society?

— I see a lot of parallels, and, of course, they are not exactly the same. I think it is really challenging to walk that line because when you are under attack, it is difficult to see the pain and horror of anything else that is going on. So, I think about that, and certainly, it does exist. I have had the pleasure of sitting and spending time in solidarity with people from Gaza who recognize the similarities between what is happening in Gaza and what is happening in Ukraine. Certainly, nowhere is a monolith. I am not going to say that is how everyone feels, but I have had that privilege of actually having those conversations with people from Gaza. But I do think that comparing is tough to do because there are differences.

Of course, I think anytime we get into the sort of the ‘trauma Olympics” — who’s got it worse — we are destined to fail. So, I think it is really about sitting with people, really connecting with people, and understanding them. Where are our similarities? Where can we stand together? Where do we need to center one thing or another? It is the same thing, I think, that happens in the left and in larger movements, at least in the United States, and maybe globally. Generally speaking, as we get siloed into our issue, we tend to be like, “Oh no, nothing else matters,” instead of recognizing that actually, when we unite across those issues and fight for things that maybe do not directly impact us, we are stronger, and we have the power to actually win big, global victories.

And so the parallels that I see — I think we have named some of them already. The Palestinian people have, for 75 years, been occupied by an outside imperialist, Western-funded nation. And I think that is one of the spaces where it becomes difficult for the left, because the U.S. has done so much to fund Israel. But we have done very little to fund Russia. It goes back to that same idea: if the U.S. is funding it, it must be bad, and if the U.S. is not funding it, it must be good. It is just overly simplified. Ukraine has, for centuries, fought for its freedom. At this point in time, it has not been the same length of occupation. Crimea was annexed in 2014. That is not 75 years, and it is not the whole country. There are differences, but there are also very real similarities. In both instances, the Palestinian people deserve sovereignty. They deserve not to be occupied. They deserve not to have people starving them or bombing them. And when I look through Ukrainian history, there is a history of Russia doing very similar things with the Holomodor, with what is happening right now, with the annexation of Crimea. So, parallels? Yes. Exactly the same? No.

You know, I think another big difference is that Israel was sort of artificially created by the West — in my most cynical view — as a way to open a door into the Middle East for Western forces. And in my least cynical view, it was created as an ethno-state. I do not know that ethno-states are ever healthy. That is not the case with Russia. Russia is not an ethno-state, and it was not created in that same way. So yes, there are definitely differences.

As for how to bring this to the attention of American society — I mean, I think we just have to talk about it. We have to have conversations with people. We have to be willing, when we are able, to take the bold, possibly unpopular stance. I certainly have, with the platform that I have, stood in public spaces, made those parallels, and been called names for it. And that is fine.

If people want to be nasty to me because I see those parallels and want to name them, I have the privilege of being able to do that. I have the privilege of being able to say, “No, I disagree with what the government is doing” or “I disagree with what this political party is doing.” Not everyone has that.

So, I think we just — the message has been so strong — we cannot stop talking about Palestine. We cannot stop talking about Ukraine.

— In recent years, some American leftists and trade union activists have shown solidarity with Ukraine not only by issuing statements, but also through practical actions — delivering humanitarian aid, organizing delegations to Ukraine, helping refugees, and so on. In your opinion, how should such solidarity campaigns develop — not only with Ukraine as a whole, but foremost with the Ukrainian working class, trade unions, and the Left movement? Why are such campaigns significant for Ukraine, and why are they meaningful for American society and American left progressive movements themselves?

— I think they are meaningful for global society, because they allow us to connect in a grassroots way that envisions a world where everyone has their needs met. I certainly cannot think of a single country where it is happening right now. Well, certainly, there are some that I think do it better and some that do it worse. But I think the American left, and probably the global left, is woefully behind in recognizing and accepting that, whether we like it or not, the world is globalized. The fascist, imperialist, capitalist forces are globalized. They are looking at the exploitation of workers and the planet as just a means to make more money. The only way we defeat that is solidarity and connection. I am not saying that people should not still be doing this, but it is no longer going to be enough to organize our workplace into its own little union.

That is really important, and you should organize your workplace into a union if you are able to do so. But it will not be enough unless we are also organizing globally, because the oligarchs and the fascists are connected around the globe. So, that is why I think it is meaningful. Not just for American society, but globally, for the future that we can live in. In terms of why it is particularly important in Ukraine — we have seen this time and time again, and it is already happening in Ukraine — a war is used by vulture capitalists to buy up land and resources and ultimately to occupy a country that then never is able to bounce back. The austerity gets worse and worse and worse over time. So, I think it is particularly important to be connected now with the Ukrainian left, the working class, the trade unions — to be thinking about a leftist future for Ukraine after this war. It is not about going back to what it was, because you cannot, and not about going toward what so many countries are coming out of war with, which is actually something worse. But instead, to take the opportunity of this horrific thing that has happened to rebuild Ukraine and to make it better — Ukraine that is grounded in the needs of the many Ukrainians, that is grounded in worker’s rights and anti-corruption, and is grounded in a future that every Ukrainian can believe in. I think there is hope in that, and I have found so much hope in connecting with the folks who are there on the ground, trying to do their work, recognizing that now is the time to do that, not when the war is over. Solidarity means doing everything we can to prevent what is happening — and that is critically important. I think it is really critically important for the American left, which is part of why it is so frustrating to me because we do have an alternative here.

We have an alternative to what we have seen over and over: the U.S. goes in, takes the resources it wants, and leaves. We have an alternative: to go in, as American leftists, to build solidarity and something different from Ukraine to the United States, and say, “No, no more of that.”

— Thank you. I want to add one more question about the American political situation. Right now, we are facing a very dangerous moment as the U.S. is seeing attacks on basic social and political rights coming from the Trump administration. We are also witnessing a continuing decline in support for the Democratic Party, which has no clear strategy on how to resist the current administration. Of course, you have your own vision and perspective, especially because you were endorsed by the Democratic Socialists of America. Also you are connected to the broader leftist movement. What is your vision of the current situation, and more specifically, what do you think the strategy for resistance should be?

— Absolutely, I mean, the current situation, as you have framed it perfectly, is dangerous. It is leaning fully into authoritarianism and fascism. It is creating chaos and fear, which are the point. Moreover, it is creating despair, which again is the point. These are symptoms, not the actual problem, which is the material conditions of everyday people. We know this from history. We know that when Hitler rose to power, it was because everyday Germans were struggling, were not able to put food on their tables, were not able to meet their basic needs. People in despair are easier to propagandize and weaponize. What I see in the U.S. is that Donald Trump, and those called by Trump, have said, “Yes, we see your despair. We hear about your struggle.” What happened is the Democrats’ fault. I cannot really call them the left party, which in most places in the world would be the center-right party at best. What they have failed to do is offer any hopeful alternative. In fact, they have also failed to even acknowledge the problem. But I have to show the whole scene. The right is saying things like, “Yep, I know things are bad, and it is the immigrants’ fault,” while the democrats response is, “No, it is not really like that. Listen to what economists say. The economy is great! Look at the stock market!” They won't even acknowledge that there is a real problem for people.

And when I think about the path forward, I believe the left is the only path forward. It is the leftist movement that meets people's needs, creates mutual aid networks, and ensures everyone can put food on their table — that is the only way we defeat fascism. And that is going to take a whole organization to fill the vacuum, because there is no unified leftist political mechanism in this country. This is a byproduct, of course, of the two-party rule system. There are lots of laws and rules that make it extremely difficult to build such a movement in the limited time we have. Electoral politics alone will not save us. The system is structured to maintain power in the hands of the people who currently have power. And I think it also takes a lot of inside and outside organizing work.

I am the only socialist in the Senate, and I have won socialist policy there, not because I convinced 29 other people to be socialists, but because we were able to frame it pragmatically and to mobilize enough outside pressure to make inaction impossible.

We know that is true throughout history. I mean, the president who signed the Civil Rights Act was a segregationist. He did not suddenly stop being a segregationist. There was so much public outcry that it became politically impossible for him not to sign it into law. I think we have to work with one foot in the door of those structures, but with a lot of feet outside the door to move the political narrative back left. We know that is what people want. The election results showed us that that is what people want. The ballot initiative wins show us that that is what people want. And we have to start working in a more unified way to make it politically impossible not to go in that direction. Because frankly, what Donald Trump is peddling is faux populism. What we need is real leftist populist policy that works for everyday people without the nationalist, fascist underpinnings of where we are actually heading.

I mean, if I have an image of my perfect world, my perfect world is this sort of socialist world in which everyone has their basic needs met, in which the government is doing what I believe its job is — making sure that people are not harming one another.

Because we live in a world where corporations are harming people, and no government in this world fully meets those responsibilities. So, I think it is time we stood together and made them.

Мы намерены продолжать работу, но без вас нам не справиться

Ваша поддержка — это поддержка голосов против преступной войны, развязанной Россией в Украине. Это солидарность с теми, чей труд и политическая судьба нуждаются в огласке, а деятельность — в соратниках. Это выбор социальной и демократической альтернативы поверх государственных границ. И конечно, это помощь конкретным людям, которые работают над нашими материалами и нашей платформой.

Поддерживать нас не опасно. Мы следим за тем, как меняются практики передачи данных и законы, регулирующие финансовые операции. Мы полагаемся на легальные способы, которыми пользуются наши товарищи и коллеги по всему миру, включая Россию, Украину и республику Беларусь.

Мы рассчитываем на вашу поддержку!

To continue our work, we need your help!

Supporting Posle means supporting the voices against the criminal war unleashed by Russia in Ukraine. It is a way to express solidarity with people struggling against censorship, political repression, and social injustice. These activists, journalists, and writers, all those who oppose the criminal Putin’s regime, need new comrades in arms. Supporting us means opting for a social and democratic alternative beyond state borders. Naturally, it also means helping us prepare materials and maintain our online platform.

Donating to Posle is safe. We monitor changes in data transfer practices and Russian financial regulations. We use the same legal methods to transfer money as our comrades and colleagues worldwide, including Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

We count on your support!

SUBSCRIBE

TO POSLE

Get our content first, stay in touch in case we are blocked

Еженедельная рассылка "После"

Получайте наши материалы первыми, оставайтесь на связи на случай блокировки

.svg)