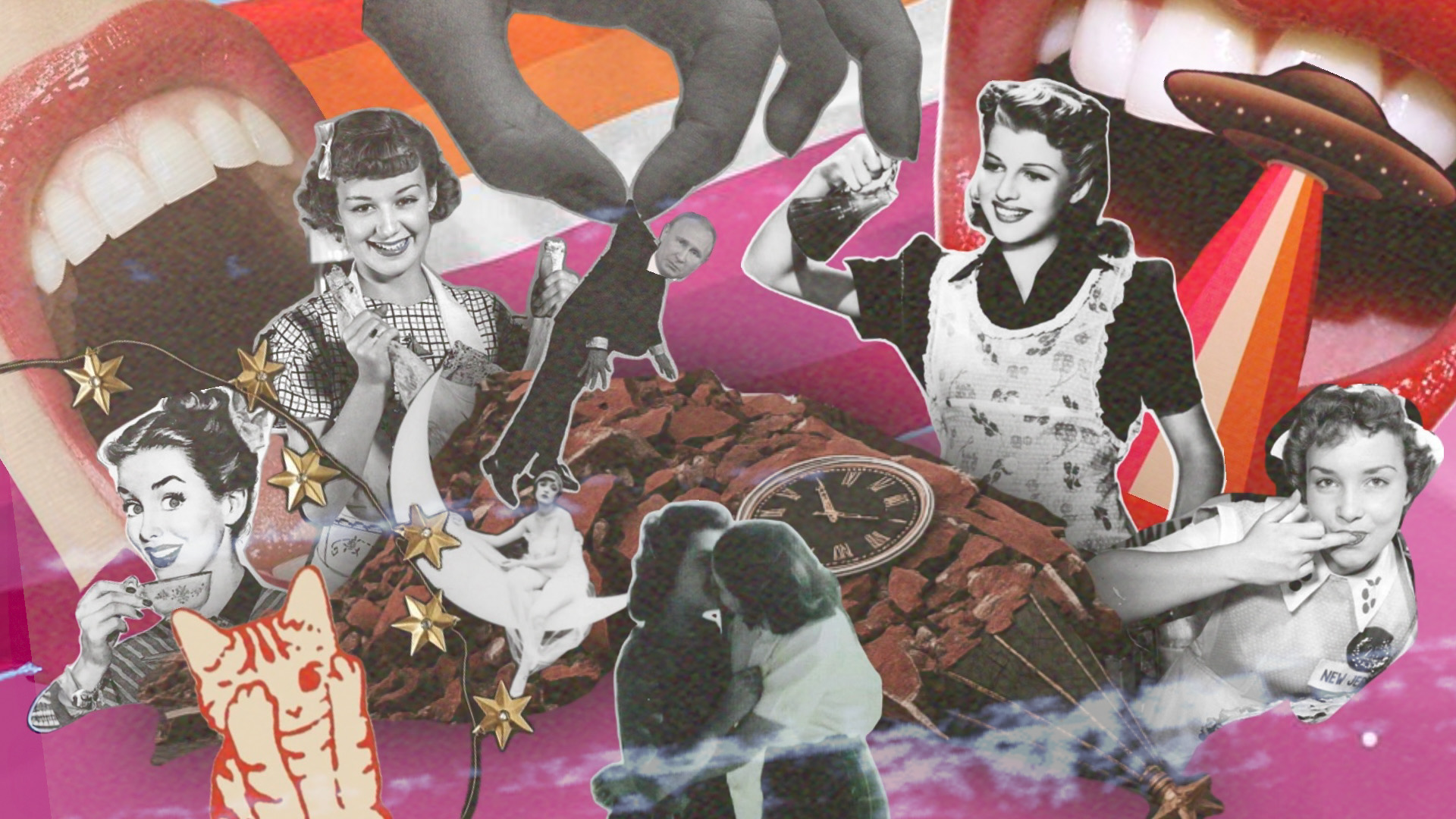

“One Day, Women Will Eat the Kremlin”

How do lesbians in Russia navigate wartime conditions, and why is claiming a lesbian identity openly such a potent act of resistance? Tatyana Kalinina, an expert on women’s and queer rights, addresses these questions by sharing the stories of openly lesbian women from Russia

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the government has sharply escalated its campaign for “traditional values” and its persecution of the LGBTQ+ community. In December 2022, the government passed a law banning so-called “LGBT propaganda” among adults. By November 2023, the Supreme Court had designated the “international LGBT movement” as an extremist organization. This effectively criminalized any public visibility or defense of queer people’s rights [author’s note: more on this can be found in the article “Rainbow Extremism” by a queer activist].

Fearing persecution, queer activists have gone underground or fled abroad. Amid this turmoil, women activists and feminist initiatives have emerged as visible centers of resistance to the war — and, notably, many of these activists are lesbians.

Patriarchy and the Invisibility of Lesbians: A Double Stigma

In a heteronormative, patriarchal society, lesbians have historically been rendered invisible. Romantic relationships between women have often been trivialized as mere friendships. Such relationships are further objectified by the male gaze — a fantasy in which two women exist solely for men’s pleasure.

This invisibility has always been bound up with risks. Many women could not openly discuss their identities for fear of repression or violence. Silence and secrecy became survival strategies. In turn, patriarchal culture has perpetuated these fears by erasing lesbians from public life and collective memory, and by reinforcing heteronormativity.

Even today, lesbians face a double stigma: as non-heterosexual people, they are targets of homophobia, and as women, they are vulnerable to sexism.

Feminist scholars argue that the erasure of lesbian experiences is a deliberate act of the patriarchy. In her 1980 work, Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence, poet and theorist Adrienne Rich wrote, “The destruction of documents and testimonies about lesbian existence has always been used to sustain compulsory heterosexuality.” This erasure has deprived women of knowledge about the “joy, sensuality, courage, and a sense of community” that lesbian relationships can offer.

Contemporary Russia continues this pattern of silencing. Lesbians are much less visible in the media than gay men. Can you name any openly lesbian official figures in politics? This void persists even though Russian homophobic propaganda typically targets gay men. In the patriarchal imagination, love between women is either nonexistent or less threatening.

To understand how the war and the current political climate affect lesbians and their sense of identity, we spoke with several women. One interviewee noted that homophobia against lesbians is deeply intertwined with sexism: “Homophobia [toward lesbians] here is so often tied to the way men objectify women. I kept hearing, ‘I don’t like gay men, but lesbians are fine because I can watch them.’”

This degrading form of “acceptance” reveals an outright refusal to take women’s relationships without men seriously. Unsurprisingly, in a patriarchal society, female subjectivity is always considered secondary or only validated through men. This explains the persistent belief that a “real woman” would never reject romantic or sexual ties with men. As a result, lesbians must continually prove that their love and partnerships are “real” and that their lives do not require male approval.

It’s no wonder that many lesbians in Russia today prefer to keep their identities private to avoid judgment, violence, or persecution. Imposed invisibility silences stories, weakens communities, and blocks collective resistance. For lesbians who also oppose war, the danger multiplies.

Lesbianism as Resistance to Patriarchy and Militarism

In Russia, simply living openly as a lesbian challenges the system. “Calling yourself a lesbian is already an act of resistance,” said one of our interviewees.

This sentiment echoes classic lesbian feminist writings. In Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence (1980), Adrienne Rich argued that a lesbian existence breaks taboos and refuses the life prescribed by men. It is a direct challenge to the male “right of access” to women. A woman who asserts her right to love women is, in effect, rejecting the patriarchal order that defines female existence in relation to men.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, radical feminists coined the term “political lesbianism” to describe this refusal — it is a conscious rejection of relationships with men as a strategy to liberate oneself from patriarchal dictates about heterosexual roles.

Patriarchy’s most aggressive form is militarism, an ideology sustained by hypermasculinity, hierarchical power, and normalized violence. Feminists have long warned that militarization fortifies male dominance, diverts resources from civil society, and endangers vulnerable groups.

Militarism thrives on rigid gender norms: men are cast as warriors and conquerors, while women are confined to supportive, subordinate roles at home. Anyone who disrupts these expectations — intentionally or not — destabilizes militarism’s foundations. By rejecting male sexual authority, lesbians defy the entire fabric of patriarchal values, of which war is a natural outgrowth.

As noted in the essay “No Pride in War: Queer Liberation and the Anti-War Movement,” our struggle is “not only against war itself, but also against the entire system of oppression that sustains it.”

The essay argues that “the logic of war produces the very systems of domination — capitalism, racism, sexism, homophobia — that we seek to dismantle.”

Therefore, to be a lesbian is to subvert the established structures of patriarchal power. By its very nature, it is countercultural — an alternative way of being that resists the authoritarian and militarized order of the present.

In today’s Russia, lesbian identity has thus taken on a deeply political dimension. When the state enforces ultra-conservative ideology and glorifies militarist patriotism, even the simple declaration “I am a lesbian” sounds like a challenge hurled at the entire apparatus of hate.

Lesbians in the Anti-War Movement

Lesbians have long been a driving force in global peace movements, even though their contributions have often gone unacknowledged in official historiographies. As early as the beginning of the 20th century, during World War I, women in romantic partnerships participated in some of the first pacifist organizations. The War Resisters League, one of the oldest anti-war groups in the United States, was founded in 1923 and led by Tracey Mygatt and Frances Witherspoon, a couple who lived together for over sixty years and devoted their lives to women’s rights, peace, and social justice.

In the 1980s, the women’s anti-nuclear movement in Britain coalesced around the legendary protest camp at Greenham Common, which was initially founded by a small group of women who opposed the deployment of U.S. nuclear missiles. The camp endured for nearly two decades, becoming an entirely female space and a magnet for feminists from around the world. Many of the women at Greenham were lesbians, and some found the courage to come out within that community.

At the time, British newspapers derided the protesters as “lesbians,” attempting to discredit them. However, this slur only strengthened their solidarity. One activist later recalled that the attacks gave her the resolve to embrace her identity and speak publicly about it.

The women’s peace movement offered a natural space for political expression. “It was a place where you could be yourself. I was a lesbian — of course I loved it there,” remembered one Greenham participant.

The contributions of these so-called “ordinary women” were anything but ordinary. As the actress-turned-politician Glenda Jackson once noted, their efforts proved to be of great significance. In fact, some political figures acknowledged that the historic agreements on nuclear disarmament at the end of the Cold War might never have been reached without Greenham Common. Years later, former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev credited “the women of Greenham and the European peace movement” with helping pave the way for the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which he signed with U.S. President Ronald Reagan that December.

These are just a few examples. Lesbians have historically played a vital, though often hidden, role in opposing war and militarism. Their contributions have routinely been erased or downplayed in public narratives. As women, they feel patriarchal oppression more acutely, and the feminist peace movement has often given them a natural platform for open expression.

Today, as war and repression have crushed Russian civil society, this historical legacy remains relevant.

In Today’s Russia

Lesbians in Russia are finding different ways to resist both war and oppression. One example of this self-organization is the growing network of mutual aid among those in exile. Two women we interviewed were forced to flee the country due to the threat of persecution.

Tanya, 25, left Russia in the summer of 2022, first settling in Georgia before moving to Argentina with her partner. After the full-scale invasion, she began supporting human rights organizations more actively. What started as small donations soon turned into full-time volunteer work for OVD-Info, a group that documents political arrests in Russia.

“There was a moment when I had to contact OVD-Info myself because I didn’t know what to do,” Tanya recalls. “My mom called me at midnight and said, ‘Tanya, two men in riot gear are banging on my door, asking for you. What did you do?’ I said, ‘I have no idea.’ We decided that I needed to leave the country quickly. I still don’t know what that was about.”

By 2024, Tanya was volunteering with the Labyrinth project, helping create guidelines for women facing domestic violence in exile. She also continued working with a Russian-language feminist media outlet. For Tanya, it was crucial to combine feminist analysis with practical, hands-on help.

Volunteering gave her a sense of purpose, even far from home, though it often left her feeling drained. “Activism helped me stay afloat,” she says. After the war began, most of her social circle fell apart.

She says, “I basically lost all my friends. It’s difficult to maintain a connection from a distance, especially when your problems are so different. You’re in exile, while they’re still back home pretending that nothing’s happening.”

Even after leaving Russia, Tanya continues to speak openly about her identity and against violence. She says that she only truly accepted her lesbian identity after leaving the country. Coming out became both a personal catharsis and a form of protest against the regime.

Alina, another woman we spoke with, stayed in Russia until 2024 but eventually emigrated as well. She now lives in Tbilisi. Before the war, Alina was not an activist. However, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, everything changed. She witnessed the repression of anti-war protesters, the exodus of close friends, and the destruction of independent media outlets. The signs were clear: staying was dangerous.

After leaving Russia, Alina decided to help others facing similar challenges. Today, she works for the Ark (“Kovcheg”), the largest human rights initiative supporting anti-war Russians in exile. Since its founding in spring 2022, the project has become a lifeline for dissenters, offering temporary housing, legal aid, and psychological support.

Alina joined the organization about a year after she relocated and felt safe abroad. She is openly lesbian and a feminist. She now contributes to the resistance in quiet, everyday ways, such as helping people navigate bureaucracy, find housing, and attend support meetings. This kind of “invisible labor” often goes unnoticed, yet it is essential to the survival of Russians in exile. Through such solidarity, the diaspora, including its lesbian community, preserves its resilience and dignity, defying the state’s attempts to divide and intimidate them.

Inside Russia, lesbians who have chosen to stay also find their own ways to resist.

Ella, 23, lives in St. Petersburg. She is not part of any formal anti-war movement, but she tries to create a supportive community around herself. Ella cut ties with her family due to domestic abuse and moved to the city alone, even before the war began. Living independently, she fully embraced her lesbian identity and stopped hiding it.

After February 24, 2022, many of her friends left the country, leaving her feeling isolated. Instead of despair, Ella turned to work that fosters solidarity and aligns with her values. She now works as a massage therapist, nanny, and volunteer for youth projects. Ella admits that the war has “tightened the screws” for all queer people; any wrong move could lead to trouble.

Despite the hostility, she refuses to stay silent about who she is. She believes that openness attracts allies. Her form of resistance is simple human perseverance: renting an apartment, working, helping others, walking the dog, loving who you love, and not letting fear destroy that life from within.

The war has exposed a new layer of vulnerability. She explains, “I feel constant pressure because I can’t pretend to be straight. I’m someone who just can’t disguise herself.”

Another woman, who requested anonymity and identified herself as Noemin, is an activist, social worker, and educator based in St. Petersburg. She is part of the Feminist Anti-War Resistance (FAR), a decentralized network of activists in and outside of Russia that was founded on February 25, 2022 — just one day after the invasion began.

FAR was among the first to publicly oppose the war and state violence. Since then, FAR has faced relentless repression. In December 2022, the Ministry of Justice labeled the group a “foreign agent,” and in spring 2024, it was declared an “undesirable organization.” Yet, thanks to people like Noemin, independent and anonymous FAR units continue to operate inside Russia.

Noemin also participates in an feminist initiative and works with migrants and refugees, including Ukrainians. “Once the war began,” she says, “it became clear that I couldn’t do anything except social work. Nothing else made sense anymore.”

Before the war, she participated in queer festivals in St. Petersburg. “Now, of course, everything is different,” she says. Even finding medical care as an openly lesbian woman has become a struggle. She explains, “Even friendly doctors are afraid of the consequences and have to be cautious.”

The war has also transformed how she relates to her identity. “Before, I tried to ‘normalize’ my life to show that we’re just like everyone else. I didn’t want being a lesbian to define me. But now visibility feels crucial. I find myself wanting to talk about it more and show it more.”

She now wears a rainbow pin, casually mentions her sexuality, and refuses to self-censor. She says, “Sometimes it’s as small as holding my girlfriend’s hand, kissing her downtown, or dressing gender-nonconforming. I don’t know if everyone can do it, but — honestly? I don’t give a fuck anymore.”

For Noemin, any open display of queer identity in Russia has become inherently political and unsafe. What once seemed like an absurd law — the 2013 ban on “gay propaganda” — now implies prison terms. Publishing queer books, supporting queer organizations, or even keeping a rainbow flag at home can be considered extremism. “We were writing a safety protocol the other day,” she says, “and the biggest question was what we should do with this queer flag behind me, because the punishment for displaying it now is almost as harsh as for blowing up a railway — it’s terrifying.”

She mentions the case of Andrei Kotov, who died by suicide while in pretrial detention after being charged with “extremism” for organizing gay travel tours.

She says, “Even for Russia, this kind of cruelty is hard to process.”

Noemin explains that the war has made life unbearable for the already precarious queer community: “It’s gotten even worse. Lesbians were already marginalized. Now there’s danger everywhere — they can take your child away from a same-sex family for no reason.”

Before, she could say, “Yes, I’m a lesbian, but I’m just a regular person like everyone else.” Now, she feels that simply existing is an act of rebellion. Noemin says, “You wake up wearing an invisible superhero costume — like the Zapatistas’ bandana — a symbol of protest. Even if you don’t go to rallies or belong to any organization, living as a lesbian is already a form of protest. The state has made you a criminal simply for existing.”

Noemin says the war has politicized every fragment of her daily life: “I used to draw lines, keep my personal life separate. Now that’s impossible.”

She must constantly discuss contingency plans with her mother, partners, and friends. They must know what to do in case of arrest or if the police approach them. They must also decide whether it’s safe to hold hands or kiss in public. Even her therapy has changed; she needs a psychologist who understands the political context of her life. “There’s almost no space left for me,” she admits, “but I have to keep working and living, because until the war ends, survival itself is resistance.”

Aside from activism, Noemin writes poetry, which is another form of protest and solidarity. At one point in our conversation, she says, “Lesbianism, ontologically, contradicts almost every system of power and oppression. It’s such a powerful tool. No, we didn’t choose it. It’s not fair to demand that people use it politically, but if they did, it would be explosive. Literally.”

In one of her poems, she envisions a utopian, apocalyptic scenario of women and lesbians rising up to destroy the old world and rebuild a new one from its ruins:

I/we are revolutionaries,

I/we know that one day women will eat the Kremlin

and smear their tongues with crumbs of red brick,

and tiny lesbians will make soup from the deputies,

and giant lesbians will set the Moscow Ring Road on fire (look: Moscow’s burning, that’s me, that’s me)

and they’ll go stomping with huge feet over presidents and policemen,

and lesbians, dykes, and butches will build communes and cities

ruled only through mutual obedience,

and they’ll kiss the forests that will never again be cut down,

and hold their sisters, lovers, friends, comrades, rebels, revolutionaries

so tightly that calluses bloom in the crooks of their arms.

Admit it — don’t you want that too?

Solidarity, the Value of Community, and Peace

What unites all of our heroines, who are different in terms of their experiences, ages, and geographical locations, is the understanding that lesbianism, in the broadest sense, has become part of anti-war resistance for them. Some participate directly in protest movements or support human rights organizations, while others simply live openly and care for those around them. In today’s Russia, both are acts of defiance against a militarized authoritarian order.

Despite the fear and risks, each woman finds sources of support — in herself and in those around her. When Ella sank into a deep depression after her close friends fled the country — she had literally helped them pack their bags before their hurried departure — what saved her was friendship. She says she no longer holds any illusions about the “bright side” of what’s happening; the only thing that matters now is not being alone in the dark. When asked what keeps her going in exile, she answers without hesitation: “I really need communities and safe spaces — places where you can come and cry, rant, or just talk. I feel how vital that is, how much it helps you stay at least somewhat sane.”

Solidarity and understanding are also what sustain Noemin. She emphasizes that it’s social bonds and a sense of camaraderie that keep her afloat. When there are friends and allies nearby — even those who share only part of her experience — there’s still hope and a reason to keep going. Like others, she finds meaning even in small victories: “Even if activism helps only us for now, that’s already an achievement. There are ten of us who help each other — and ourselves.” She believes that a community like that will preserve itself and its values through years of hardship.

Lesbians may be invisible to the state, but not to each other. Through informal networks, chats, and word of mouth, they find comrades both in Russia and in exile. Small circles of mutual aid continue to emerge, ranging from home-based feminist gatherings to online peer support groups. This horizontal solidarity is a powerful weapon against the despair and isolation that the authorities seek to impose.

In a deeper sense, lesbian love and friendship are alternatives to the logic of war. War thrives on hatred of the “other,” on domination, and on violence. By their very nature, lesbian relationships reject male supremacy and embody equality, reciprocity, and care — values that have no place in a militarized culture. In this sense, every happy lesbian couple in today’s Russia is a small island of peace and resistance.

It is crucial to acknowledge the contribution of lesbians to the broader anti-war and human rights movements. We work as volunteers, coordinators, and journalists; we help refugees, organize humanitarian aid, and support political prisoners. Often this labor remains invisible, hidden behind gender-neutral descriptions like “activist work” or “initiatives of Russians against the war.” Yet, behind these neutral phrases are real women with real stories — including lesbian stories.

Our motivation often stems from a familiar place: the experience of oppression itself. We know what discrimination feels like, which is why so many of us react so strongly to the current state-sponsored injustice and violence. Being a lesbian in Putin’s Russia is an act of courage. To be a lesbian who speaks out against the war takes double the courage.

This choice often comes at a price: estrangement from family, loss of work, exile, or constant fear. Yet many of us make it, because otherwise we would betray the very values that define us.

Lesbians need peace!

Мы намерены продолжать работу, но без вас нам не справиться

Ваша поддержка — это поддержка голосов против преступной войны, развязанной Россией в Украине. Это солидарность с теми, чей труд и политическая судьба нуждаются в огласке, а деятельность — в соратниках. Это выбор социальной и демократической альтернативы поверх государственных границ. И конечно, это помощь конкретным людям, которые работают над нашими материалами и нашей платформой.

Поддерживать нас не опасно. Мы следим за тем, как меняются практики передачи данных и законы, регулирующие финансовые операции. Мы полагаемся на легальные способы, которыми пользуются наши товарищи и коллеги по всему миру, включая Россию, Украину и республику Беларусь.

Мы рассчитываем на вашу поддержку!

To continue our work, we need your help!

Supporting Posle means supporting the voices against the criminal war unleashed by Russia in Ukraine. It is a way to express solidarity with people struggling against censorship, political repression, and social injustice. These activists, journalists, and writers, all those who oppose the criminal Putin’s regime, need new comrades in arms. Supporting us means opting for a social and democratic alternative beyond state borders. Naturally, it also means helping us prepare materials and maintain our online platform.

Donating to Posle is safe. We monitor changes in data transfer practices and Russian financial regulations. We use the same legal methods to transfer money as our comrades and colleagues worldwide, including Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

We count on your support!

SUBSCRIBE

TO POSLE

Get our content first, stay in touch in case we are blocked

Еженедельная рассылка "После"

Получайте наши материалы первыми, оставайтесь на связи на случай блокировки

.webp)

.svg)