Labor Protest in China

What is remarkable about the Chinese strikes of recent years? What regions and workplaces are seeing a working-class identity emerge? Independent researcher Sergey Shlyapnikov breaks it down

The global system has entered the final stage of financial expansion, increasingly leading to armed conflicts at the borders of major players. Russia has opened Pandora’s box by invading Ukraine; Israel has decided to complete its Gaza, Lebanon, and Iran operations once and for all, while the US, tired of its supreme peacekeeper mission, is blackmailing Venezuela. We are past the winter-is-coming stage; the white walkers are already storming the wall.

Amid all of this, China finds itself in a difficult position. On the one hand, it is about ready to compete for global hegemony, as demonstrated by economic indicators. On the other hand, China’s ambition is undermined by its status as a “global factory,” as its dependency on labor-intensive sectors renders it vulnerable in multiple ways.

One of China’s weak spots is the social tension that inevitably arises within an industrialized economy of this scale. The global outsourcing of production to China, as seen in the past decades, has made the country the potential epicenter of global workers’ protest. As industrialization progresses, groups of workers have emerged that are capable of self-organization and collective action. The question is if they could become a political force under the right circumstances.

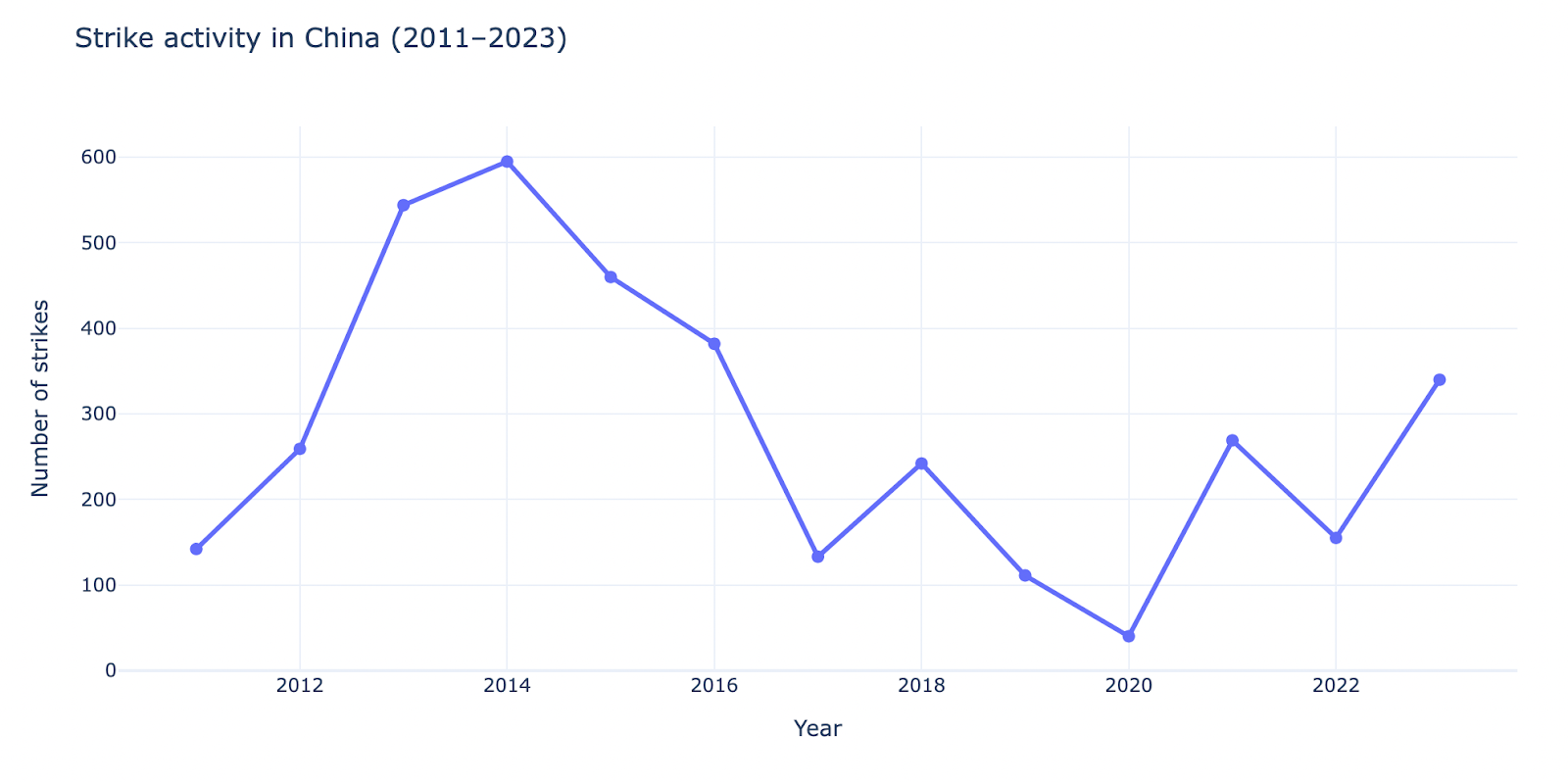

Worker Strikes in China Over Time

In the past ten years, the frequency of strikes in China has remained largely the same, averaging at 272 strikes per year throughout the country. This is a modest figure, but comparing year-to-year data reveals significant changes over time. The numbers show a period of increased activity in 2012–2016, peaking in 2014 and declining in later years. The decline was due to the toughening of domestic policies under Xi Jinping. The closure of non-governmental organizations, new laws restricting grassroots civic activity, and political persecution of activists all eroded the infrastructure of workers’ mobilization.

Note: All data are from China Labor Bulletin (unless otherwise indicated); calculations are by the author, available on github.

The average number of strikes in China is comparable to statistics for Germany and the USA (312 and 466 strikes, respectively, in 2023). Unlike these two countries, however, China lacks the key institutions regulating employment relations: it has no independent unions and no established mechanisms of labor arbitration and collective bargaining.

The change in the number of strikes in recent years indicates the heterogenous situation of the Chinese working class, as described by Ching Kwan Lee: it is split into workers in the Northeast who rely on the state and avoid any conflict with their management, and East Coast workers who seem determined to collectively assert their rights.

The situation on the East Coast is a manifestation of a well-known pattern: in the absence of industry-wide union federations or structures for labor arbitration, strikes will be common but limited in scope. The country’s Northeast, in turn, has seen industrial decline and the end of the socialist contract wherein the state provided basic protection in exchange for loyalty. This has led to a certain kind of post-socialist passivity: there are hardly any strikes occurring in that region, so few that it drags down the country-wide average.

The 2012–2016 round of strikes turned out weaker than anticipated. Moreover, it did not lead to the emergence of independent trade unions and other institutional forms of struggle for labor rights. But there are reasons to be optimistic: what if the protests on the East Coast were the first sign of more massive and perhaps more radical changes in the future?

It is worth taking a closer look at the situation on the East Coast in order to understand the origins, nature, and prospects of labor struggles in modern China. In the next section, I review the recent history and current state of Guangdong Province, a key region for the Chinese economy.

Economic Conditions: Guangdong Province

Guangdong is one of China’s largest and most developed provinces: it is home to 127 million people and has a GDP of $1.83 trillion, which is comparable to modern Russia. Part of the province lies in the Pearl River Delta and is one of the most densely industrialized regions in the world.

Guangdong’s transformation into a major Chinese economic center dates back to the late 1970s. Located just a few dozen kilometers from Hong Kong, one of the “Four Asian Tigers,” the region became a testing ground for Deng Xiaoping’s policy of “reform and opening up” after the party leadership at the time realized how far China lagged behind its rapidly growing neighbor and decided to undertake major economic reforms.

For these reasons, the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone was established in Guangdong in 1980. The government launched a small controlled experiment, which proved successful. Abandoning the people’s communes, granting work permits without residence registration, and expanding economic autonomy for enterprises freed up the labor force and laid the foundations for export-oriented industrialization. By 1984, 14 coastal cities had been granted special status.

Proximity to Hong Kong and the influx of millions of migrant workers from the mainland have transformed the Pearl River Delta into one of the most dynamic industrial hubs in the world. Thousands of small and medium-sized factories in Hong Kong moved their operations to the mainland in search of cheap labor, mostly producing garments and footwear. Asia’s largest trading and manufacturing intermediaries, Li & Fung and TAL Apparel, established their production bases in Shenzhen, Dongguan, and Foshan. They became, during the 1980s and 1990s, a key link between major American brands (Gap, Walmart, Target, etc.) and Chinese factories, supplying the industry in Guangdong with lucrative production contracts.

Soon production moved beyond clothing and shoes. The now-famous Huawei was established in 1987, originally as a trading company dealing in telephone equipment. A year later, Foxconn opened its first factory in Shenzhen, assembling plastic electronics components. This marked the beginning of a new stage in the region’s development, as its industrial specialization started shifting into producing electronics and components.

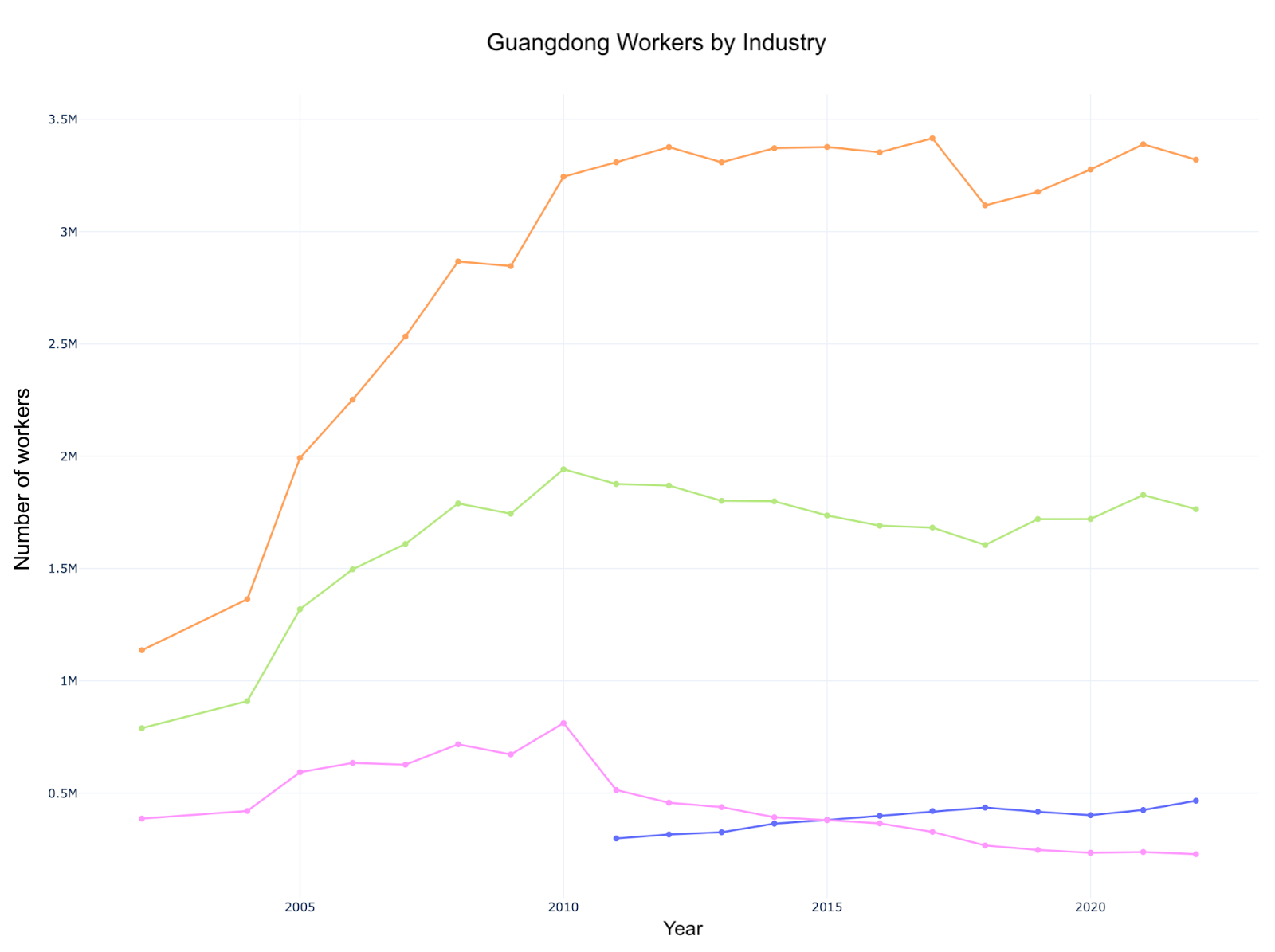

A closer look at the history of Guangdong between 2000 and 2025 reveals, apart from its continuous economic growth, two very different tendencies that prevailed, in sequence, during the two recent decades. The first period, from about 2003 to 2013, resembles Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The economy expanded, public wealth grew, but at the same time, the number of workers also grew, resulting in what Marx called “relative overpopulation,” leading to the gradual impoverishment of workers. Low wages and a huge reserve of migrant labor were the key drivers of Guangdong’s industrial growth.

Note: Orange = energy, green = electronics, pink = textiles, blue = automotive. Data drawn from the Guangdong Statistical Yearbook, 2002–2023 calculations by the author.

The situation changed dramatically in 2010–2023. This was China’s “Lewis turning point,” when the country’s surplus of cheap rural labor was exhausted and wages began to rise. Employment stabilized, while profits per worker began to rise in labor-intensive sectors.

The more capital is involved in production and the tighter the labor market becomes, the higher the profit per worker and the more capital is forced to curb its appetites. As capital accumulates, if the labor market is limited, the structural power of workers grows. And, according to some estimates, the labor shortage in Guangdong is not a temporary setback but a new defining feature of its economy.

China’s economy received a huge boost from a combination of cheap labor and commodity exports, but this model is now reaching its limits. To understand what is happening to the region’s workers, what their current needs are, and what the prospects are for the local labor movement, we need to understand who Guangdong’s workers are, how they have evolved in recent years, and how they identify themselves.

The Identity of Guangdong Workers

China’s urban population did not exceed its rural population until 2011, although this shift happened a little earlier in Guangdong. This means that China’s urban working class is quite young in the sense that it has only recently emerged. At first, new workers perceived and positioned themselves primarily as internal migrants [author’s note: this can be seen in the new poetry and literature emerging in the region since the 1990s]. As years have passed, the countryside is no longer their home, and the workers have been developing a class consciousness or, at the very least, a professional identity.

Workers at Guangdong enterprises realize that leaving employment for small business is no longer possible: business in the region is now monopolized, while rent has become extremely expensive. Going back to the countryside is not an option either, as work has become very scarce due to mass urbanization. Thus, under the current circumstances, wage labor in the city remains the only viable option to make ends meet for those who are already employed in the region’s factories.

Memes shared by young workers reveal a growing sense of pessimism. One example is the meme “Good morning, employees” that became popular in 2020. The phrase appeared in a short video by a Chinese blogger who sarcastically encouraged everyone to work from early morning to late night. The video quickly went viral and the expression turned into a catchphrase.

Interestingly, the term dǎgōng rén (wage earner), which is used in the meme, has never been part of political or bureaucratic language, although etymologically it is related to the familiar word gōng rén (worker). The term blurs the distinction between blue-collar and white-collar workers and is often associated with low-paying, thankless jobs with no prospects. The mixture of emotion and irony in the memes made the term itself go viral. In some recent memes, the dǎgōng rén have been encouraged to work harder by Mao, Bismarck, and Chekhov.

Another interesting meme features Tom the cat (of Tom and Jerry) leaving his house with a bundle on a stick behind his back; as he walks away, the ironic caption appears: “A happy worker is leaving for the factory.” Other popular phrases express the joy of being fired. One example is the meme “take the bucket and leave,” which refers to the practice of using plastic buckets to pack up one’s stuff after being laid off.

Most memes express the workers’ passive acceptance of their plight as well as a sense of disillusionment. People would like stable employment, sufficient income and a permissive schedule, but they get none of that. As shown by the campaign organized by programmers against the “996” schedule (working from 9 to 9, 6 days a week), a proper work-life balance remains elusive even for highly skilled workers.

All of this explains the sudden popularity of working-class stories, some of which may even be said to have achieved a cult status. Examples include Hu Anyan’s book I Deliver Parcels in Beijing, which sold 100,000 copies in less than a year, and Wen Muye’s film Miracle: The Story of a Simple Guy (internationally released as Nice View). The film tells the story of a young worker, Jing Hao, raising his sister and surviving on odd jobs ranging from repairing phones to washing high-rise windows in Shenzhen.

There are even video games about working conditions, such as The Majority. It simulates the everyday experience of a wage earner, including various odd job opportunities. Some aspects of the game imply social criticism and demands for changes in working conditions, such as the question of why workers should have to buy their own tools.

The proportion of experienced specialists aged 30–40 among factory workers is growing, while young people are finding jobs in the city that pay just as much (for example, in delivery services). Workers’ standards have grown, and they are willing to get by on odd jobs just so they don’t feel bound to a particular factory owner. Behind this choice lies a dream of self-realization and more decent working conditions. And although economic conditions are unfavorable, the need for self-realization is like a stretched spring that will have to be released sooner or later.

And yet the workers’ pain, their anxieties and grievances have remained the same. The situation in which workers begin to perceive themselves as subjects capable of realizing their own interests, rather than as toys in the hands of the powerful, is less a condition than a consequence of collective action. When workers act together, they begin to understand that each person’s strategy for earning a living intersects with the experiences of many others. Their identity as workers, which is formed as they become aware of themselves as the driving force of production, will be strengthened in political practice.

Over time, workers in Guangdong’s factories are coming to better understand their role in the workplace, the country, and the world at large. They play through their feelings in memes and video games, creating genuine rituals and collectively taking up public space. The problem is that the maturing of Guangdong workers and development of their self-consciousness is happening in a system that resists self-organization.

Political Constraints and Opportunities

China is currently undergoing a process of elite consolidation. This contrasts the earlier situation when former President Hu Jintao balanced between the Shanghai and the Youth League groups within the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CPC). The former faction represented the technocratic elite of the coastal regions, while the latter consisted of members of the Communist Youth League apparatus. These groups mainly competed for resources and influence within the CPC and did not have serious ideological differences. At the same time, the very existence of competition within the party served to keep its chairman’s personal ambition in check.

Since Xi Jinping took over the party, the Shanghai group has lost its influence and collective governance has become a thing of the past. The 2012 anti-corruption campaign served as the final blow to the faction, as its prominent member Zhou Yongkang became the first member of the Politburo Standing Committee in history to be arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment. Having taken control of both levers of power — the party and the military — Xi Jinping is now able to directly govern the work of many state bodies.

This consolidation of power was followed by a domestic crackdown. Authoritarian regulations adopted in the mid-2010s, including the National Security Law and the Law on the Management of Foreign NGOs, undermined the mechanisms of political mobilization. As these laws introduced new types of punishment by expanding the range of offenses, the ultimate goal was to preclude the very existence of independent organizations and to build a network of public structures loyal to the state.

It is for this purpose, presumably, that the state apparatus seeks to eliminate any alternative forms of labor organization. A telling example was the strike at the Lide shoe factory in Guangdong, which resulted in the arrest of about twenty labor activists. 2,500 factory workers went on strike for eight months against the relocation of the enterprise and layoffs. The workers also demanded that the factory fulfill its social obligations if it closed, including paying social insurance and housing fund contributions.

The factory workers were assisted by the Panyu Migrant Workers’ Center, acting as an informal trade union. The Panyu Center even succeeded in organizing a system of representation at the factory. The success of the strike drew interest from the government. Arrests followed; multiple Panyu employees were sentenced to suspended prison terms, and the center’s work in labor rights protection was effectively ended.

A similar scenario played out in 2018 in Shenzhen when local university students organized a campaign of solidarity with the employees of Jasic Technology, a company that manufactures welding equipment. After a series of layoffs, the workers attempted to legally establish a union at the company. They were supported by 50 Marxist students from various universities who formed an informal group known as the Jasic Worker Solidarity Group.

This was the first attempt at solidarity between students and workers in a long time. The students traveled to Shenzhen, participated in pickets, and helped workers with their statements. In August 2018, the police raided the apartments where student activists were gathering. Many were arrested, and some disappeared for several months. Although they were all later released, some of the students were expelled from their universities and put under heavy surveillance, including restrictions on their freedom of movement and regular interviews with the police. The Marxist Society at Peking University was not allowed to re-register. The vibrant community of activists was forced to disband.

More recently, in 2024, amid a generally quiet atmosphere, new online initiatives emerged, dedicated exclusively to labor issues and workers’ rights, including “Workers’ Facts,” “Labor News: About Modern Workers,” and “Daily Protests.” As the offensive power of the labor movement was suppressed, the activist work shifted online.

Uneven Development

China is often compared to Korea in the 1970s, when informal Korean student groups built networks of solidarity with workers, operating underground and devising various ways to support them. Initiatives multiplied, and a social explosion was brewing. Looking at Guangdong in isolation, this comparison would seem quite convincing.

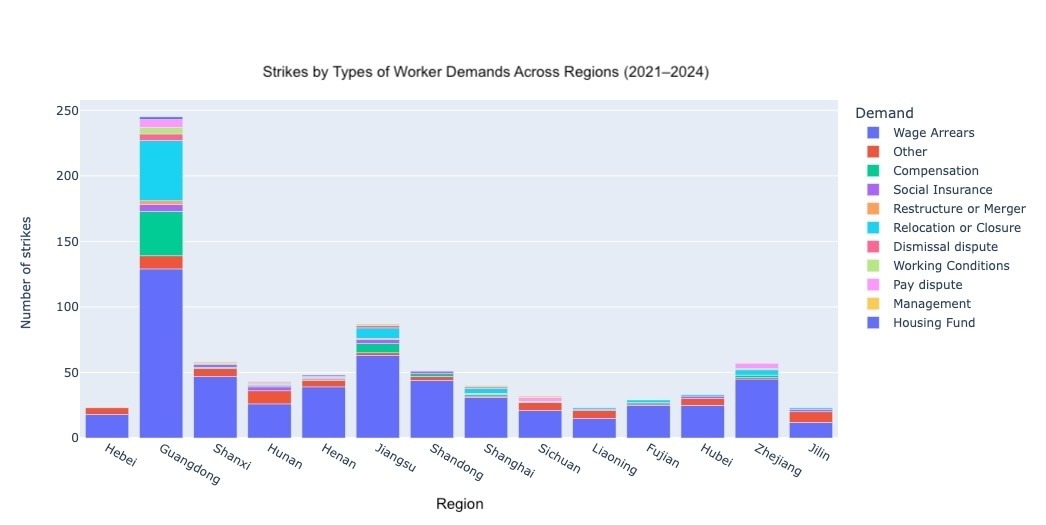

However, China is a huge country in which the deindustrialized Northeast coexists with rapidly urbanizing provinces such as Henan and Hubei. Guangdong is an epicenter of worker rebellion, whereas other inland provinces see much less of it. Protest is not entirely absent from the Northeast, but it is limited to tamer activities like petitions and local rallies.

Map of Worker Strikes in China in 2024

One of the common ways in which capital responds to wage growth is through the relocation of production.

The beginning of industrial migration dates back to the 2000s, when the authorities deliberately freed up infrastructure space for new industries. But it wasn’t until 2017 that this gradual process snowballed. The 2022 Shenzhen Manufacturing Industry Migration Review Report shows a drastic increase in the scale of this exodus: while 463 enterprises had left the city in 2017, by 2021, the number had risen to 4,344. In just a few years, Shenzhen has faced a mass relocation of the enterprises that formed its industrial core.

Most of Shenzhen’s manufacturing remains within Guangdong province, but in recent years, it has been moving further and further away from the expensive Pearl River Delta agglomeration. Manufacturers are moving to peripheral hubs like Dongguan, Foshan, and Huizhou, as well as to less developed parts of the region.

But the movement of industrial capital is not limited to Guangdong. The same 2022 Shenzhen report lists three principal locations to which companies are fleeing: first, to the Yangtze River Delta industrial cluster; second, to the central regions of Jiangxi and Hubei, where new cluster zones are forming; and third, all the way to western provinces that have been on the periphery of industrial growth for decades.

Intensifying labor protest is a factor in this relocation, alongside rising wages: faced with worker mobilization, capital is moving production to new locations in order to increase profitability. At the same time, job losses as a result of relocations also mean that the strikes of 2021–2024 were defensive in nature, mainly fought over wage delays and relocations: a gesture of despair rather than an expression of political power.

Note: Data from China Labor Bulletin; calculations by the author.

The slowdown in economic activity on the East Coast weakens the offensive nature of labor protests. And yet the protests are scaling up. As workers become more organized and capital relocates, new hotbeds of labor protest will form in other regions. Thus, the relocation of production, though it keeps undermining the possibility of forming a stable organization of wage workers in one place, ultimately creates the conditions for a new round of collective struggle—now at the national level.

Conclusions and Forecasts

The Chinese strike wave of 2010–2016 did not lead to a rise of institutions representing workers nor to a new wave of radicalization. The strikes were mostly limited to Guangdong, initiated by workers who saw themselves primarily as migrants. The times, however, have changed both for the region and for the country in general. This new period is marked by an economic downturn, which is usually associated with a decline in strike activity. At the same time, the current economic crisis is ambiguous, the economy is rather unstable, and capital relocation is uneven. This means that general uncertainty may increase workers’ dissatisfaction with their situation and contribute to their radicalization.

Also, the transfer of production to new regions of China may itself encourage the spread of protest. Industrialization usually upends conservative ways both of understanding oneself and of organizing one’s life.

The 2010–2016 strike cycle in China coincided with an authoritarian turn that proved too much for it to handle. Although the crackdown on activist organizations after the strike at the Lide shoe factory was a turning point, communities of worker activists survived. As China moves along the capitalist path and develops its industries in new regions, society will become even more complex and social contradictions even more acute. And autocracies are powerless to stop this process.

Мы намерены продолжать работу, но без вас нам не справиться

Ваша поддержка — это поддержка голосов против преступной войны, развязанной Россией в Украине. Это солидарность с теми, чей труд и политическая судьба нуждаются в огласке, а деятельность — в соратниках. Это выбор социальной и демократической альтернативы поверх государственных границ. И конечно, это помощь конкретным людям, которые работают над нашими материалами и нашей платформой.

Поддерживать нас не опасно. Мы следим за тем, как меняются практики передачи данных и законы, регулирующие финансовые операции. Мы полагаемся на легальные способы, которыми пользуются наши товарищи и коллеги по всему миру, включая Россию, Украину и республику Беларусь.

Мы рассчитываем на вашу поддержку!

To continue our work, we need your help!

Supporting Posle means supporting the voices against the criminal war unleashed by Russia in Ukraine. It is a way to express solidarity with people struggling against censorship, political repression, and social injustice. These activists, journalists, and writers, all those who oppose the criminal Putin’s regime, need new comrades in arms. Supporting us means opting for a social and democratic alternative beyond state borders. Naturally, it also means helping us prepare materials and maintain our online platform.

Donating to Posle is safe. We monitor changes in data transfer practices and Russian financial regulations. We use the same legal methods to transfer money as our comrades and colleagues worldwide, including Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

We count on your support!

SUBSCRIBE

TO POSLE

Get our content first, stay in touch in case we are blocked

Еженедельная рассылка "После"

Получайте наши материалы первыми, оставайтесь на связи на случай блокировки

.JPEG)

.svg)